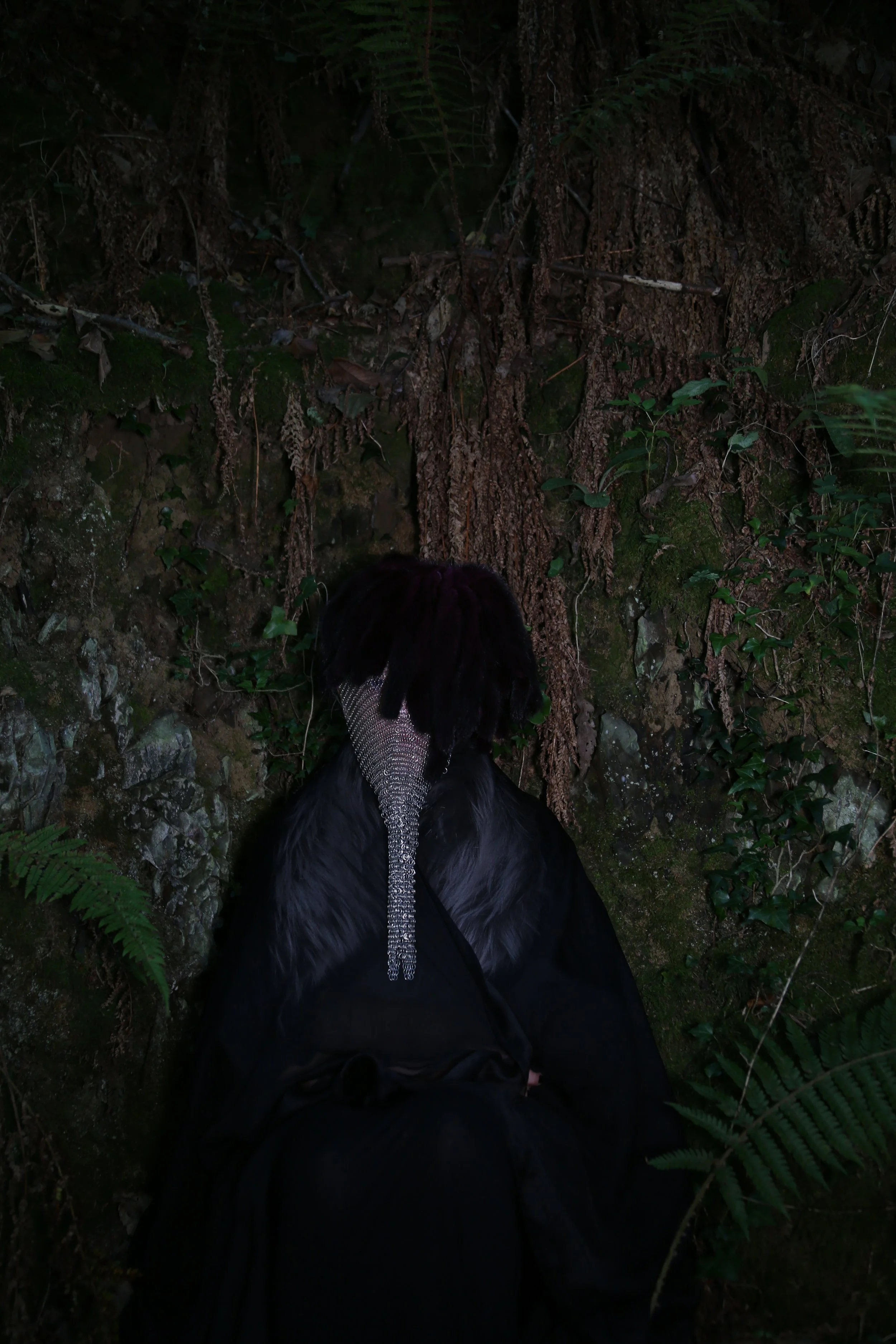

Bert Gilbert’s commission for The Horror Show: A Twisted Tale of Modern Britain at Somerset House is a work of thresholds. Not only does it mark the start of Witch, the third chapter in this exhibition surveying the dark seam of subversion running through British culture over the past half-century, but the work itself was conceived to invoke and embody perimeters and limina. How they are breached, and on what terms.

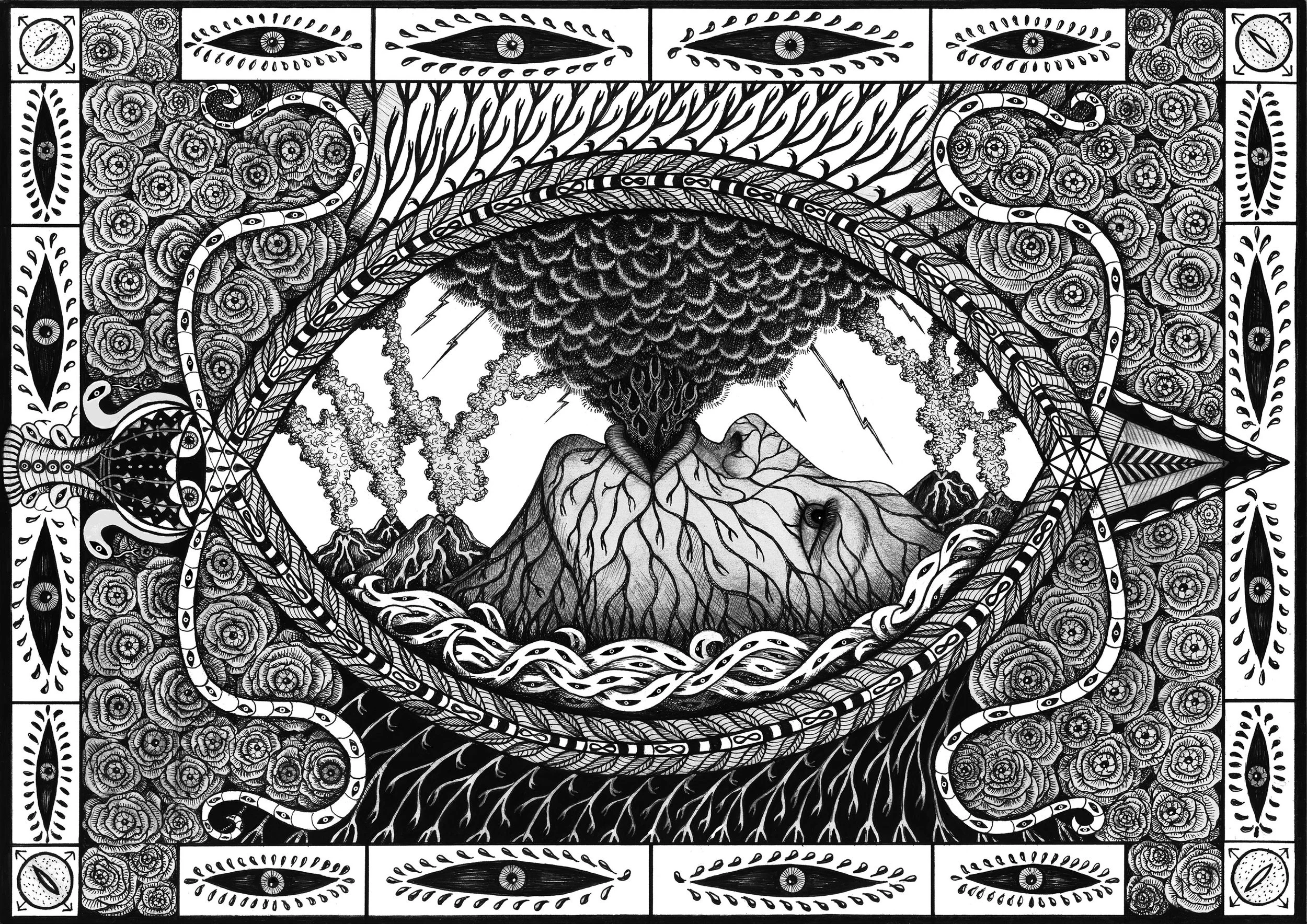

The installation brings together several key bodies of work, under the mantle of The Vesica, the geometric, almond-like shape formed by the intersection of two circles of similar radius. The figure resonates from Euclidian geometry, through da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, touching on religion, mysticism and mythology through the ages. Colloquially, the term was used to refer to the vagina, and this vulva- and womb-like shape can be found in prehistoric art, as well as in associations with Aphrodite/ Venus, the Greek/ Roman goddess of love, with offerings of fish being made in the hope of virility and fertility. In ancient Egypt, it was found in the Temple of Osiris (the god of fertility and the afterlife); the Vesica Piscis was also used to represent the vagina of the Cosmic Mother Goddess, Ma’at.

The crossing of two circles widely symbolises the union of opposites – heaven and earth, male and female, human and divine – and the almond-like shape (mandorla) is often used in Christian art to enclose images of religious figures like Jesus, Mary and the Saints. The Vesica Piscis’ (‘fishes bladder’ in Latin), resemblance to the ichthys (fish) made it a secret symbol of greeting in early Christianity; the raising of hands in the shape of a Vesica Piscis surviving today in the joining of hands in prayer.

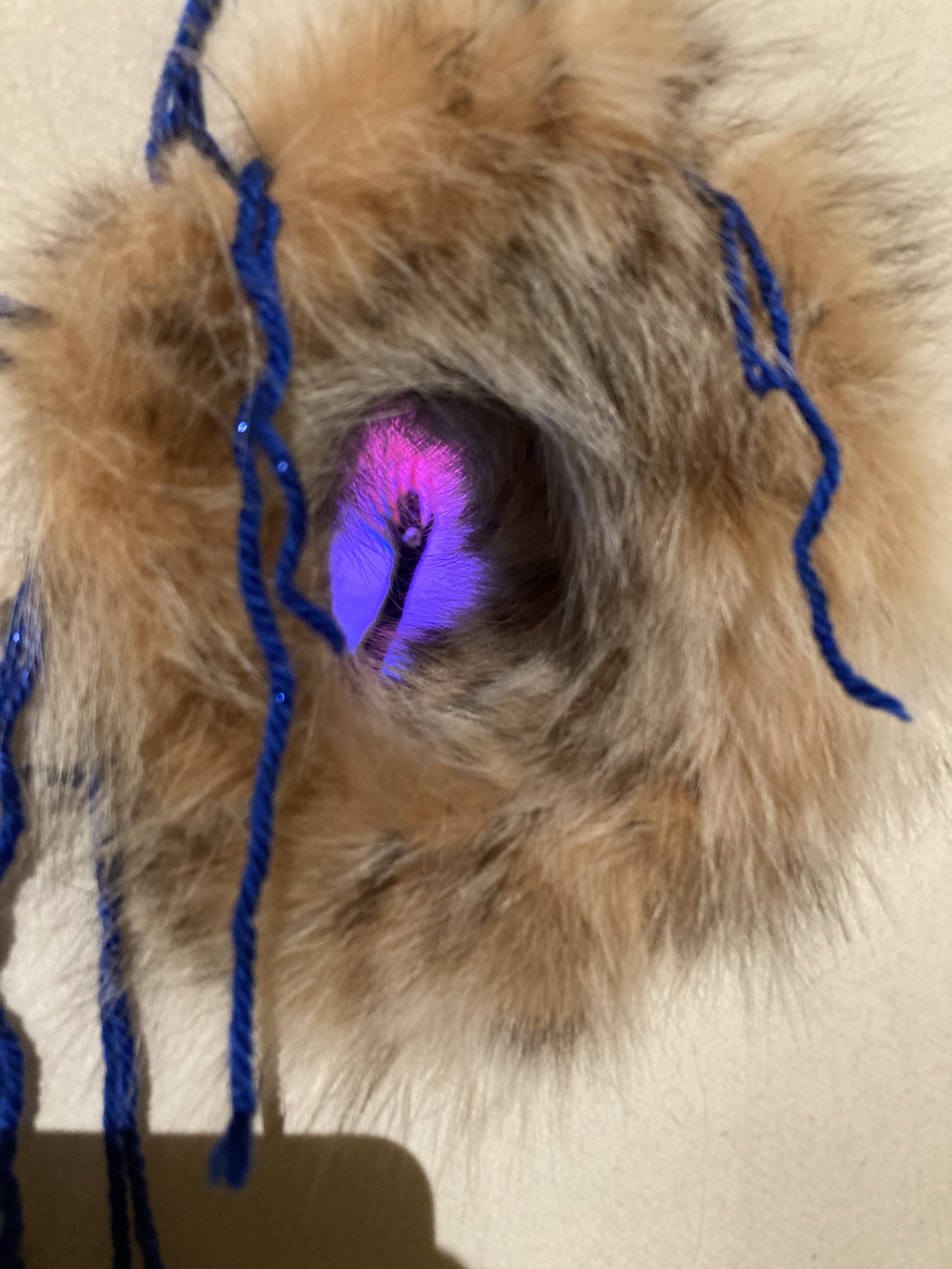

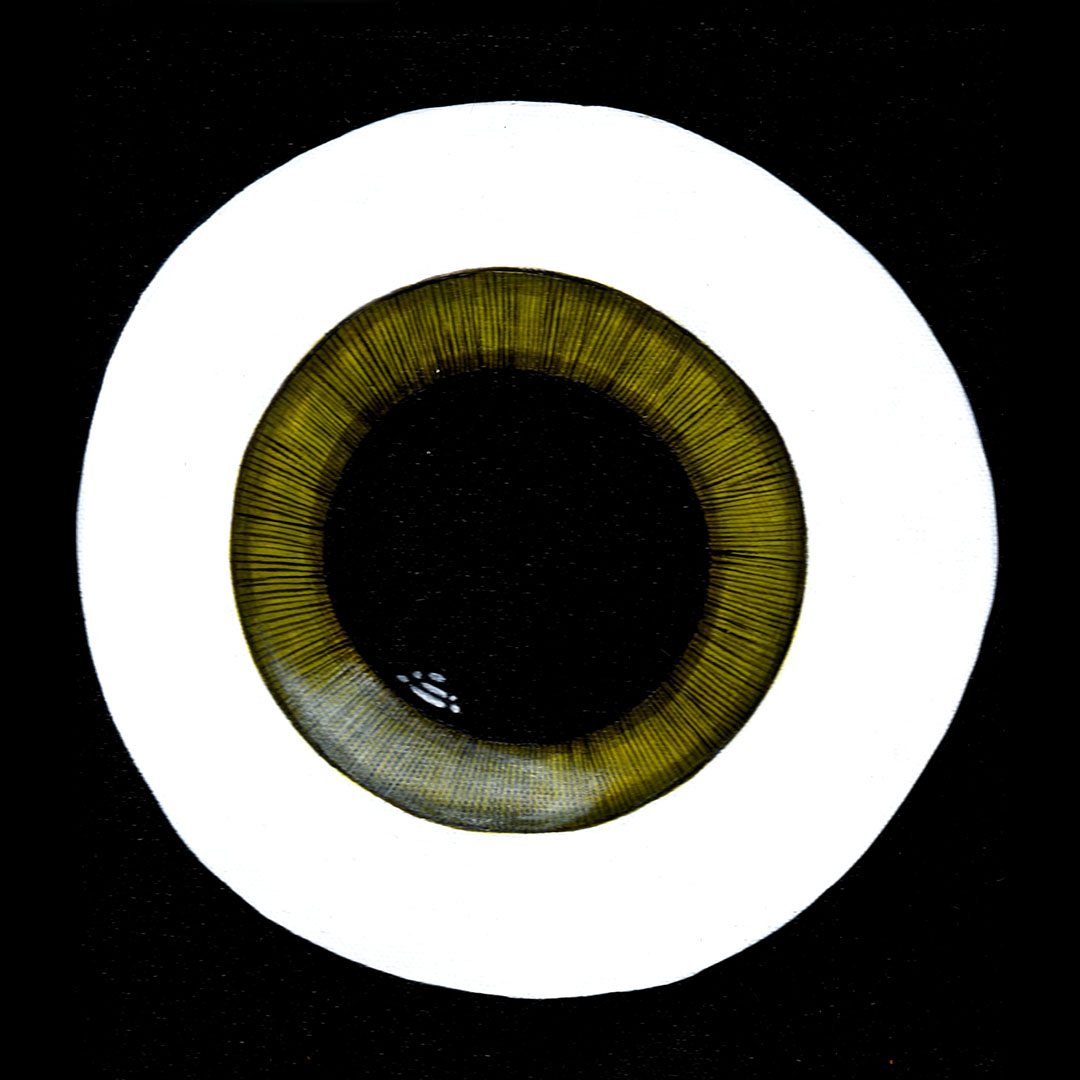

Its shape has echoes that of the amygdala, an area of the brain connected to the limbic system, and widely identified as the seat of the emotions. The Vesica Pisces’ lens-like shape has also seen it represented as an eye, a common motif in Gilbert’s work and in The Vesica itself, where it features in embroidered form as Eyecons, but also as one of her Sky Portal works.

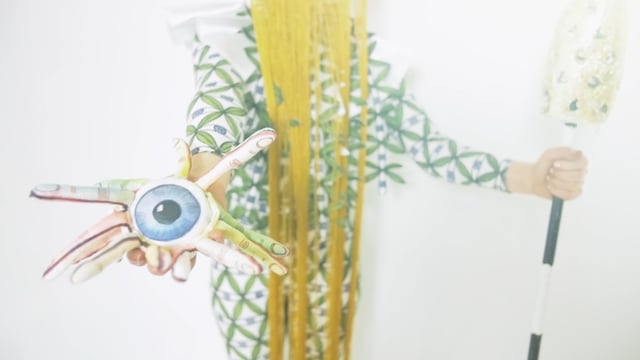

The first thing you see of The Vesica is a version of Gilbert’s Vagina Whisperers, a canvas-padded wall punctuated with embroidered vaginas, wounds and fur anuses. “I call them ‘creep holes’, the artist states. They invite the viewer to approach, challenging them to push through the soft sculpture, which throbs with a soundtrack devised in collaboration with composer Colin Waterson. Based on Parmenides’ poem, On Nature, the male narrator is inveigled into a journey by Dike, the Greek goddess of justice, moral order and boundaries.

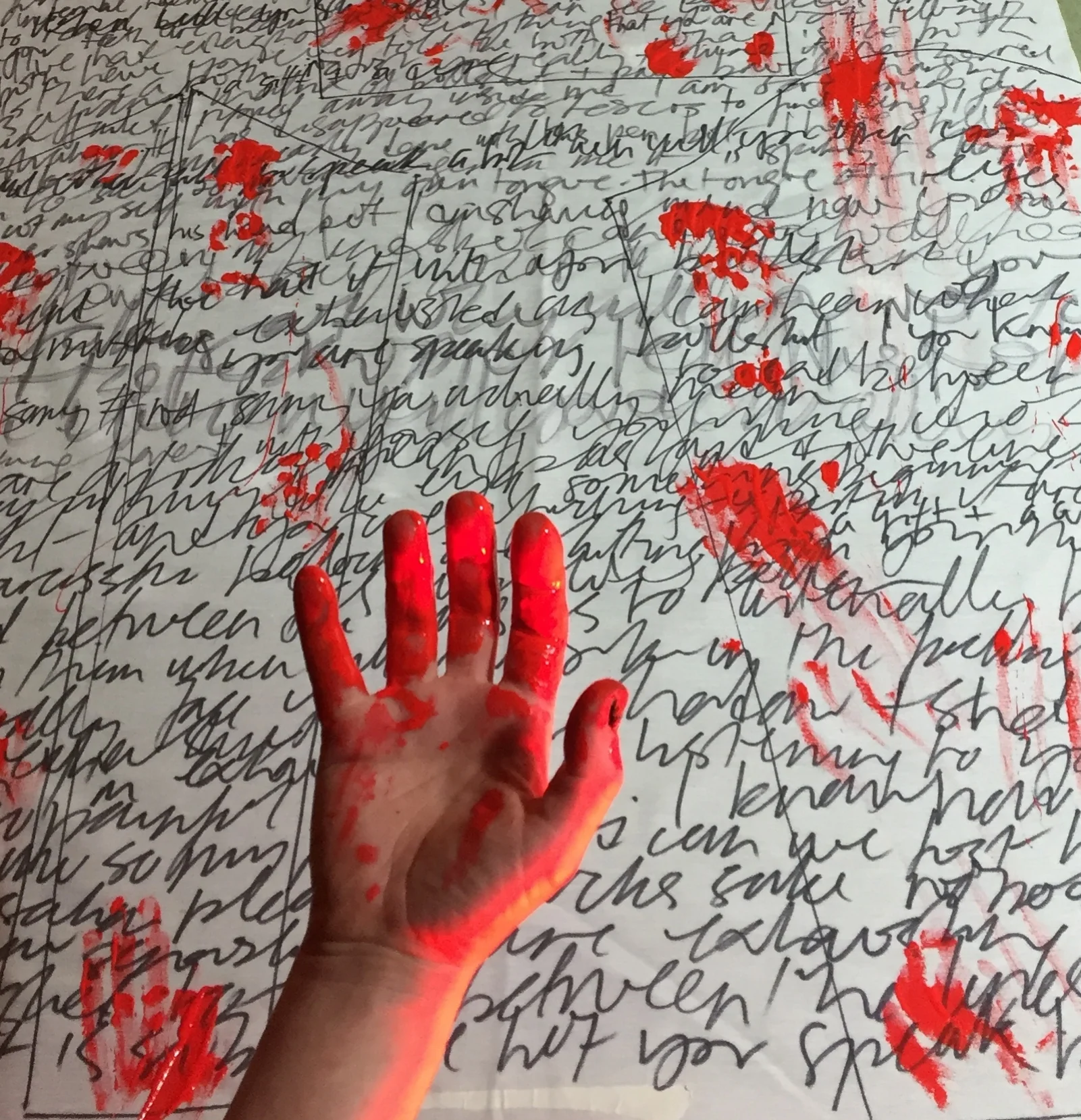

A pre-Socratic Greek philosopher, Parmenides is credited with being the father of logic; yet the ur- expression of the concept of reason is delivered in the form of the incantatory poem that forms the soundscape to The Vesica. In it, Dike guards the threshold between the world of humankind and the realm of the goddess, and she reveals to the narrator the nature of reality. Author Peter Kingsley argues that what appears at first to be counter-intuitive – a clash of form and sense – points to a duality embedded at the very centre of the creation of meaning. In On Nature, Parmenides is coaxed into the underworld by “the daughters of the sun”, to be given the gift of logic by the queen of the death. This paradox expresses the push and pull of thought in action, informed by the tangible and the intangible.

Designed to be recited, the dactylic hexameter of the poem has the physiological effect of bringing the heartbeat and breathing rate into harmony. Waterson has taken his cue from these cadences, to create an esoteric soundscape accompanying a female voice reading of the poem in Ancient Greek. Their shuddering, orgasmic qualities are heightened by wearables, embedded into the sculpture to enhance the sub-frequencies running through the track, evoking altered states.

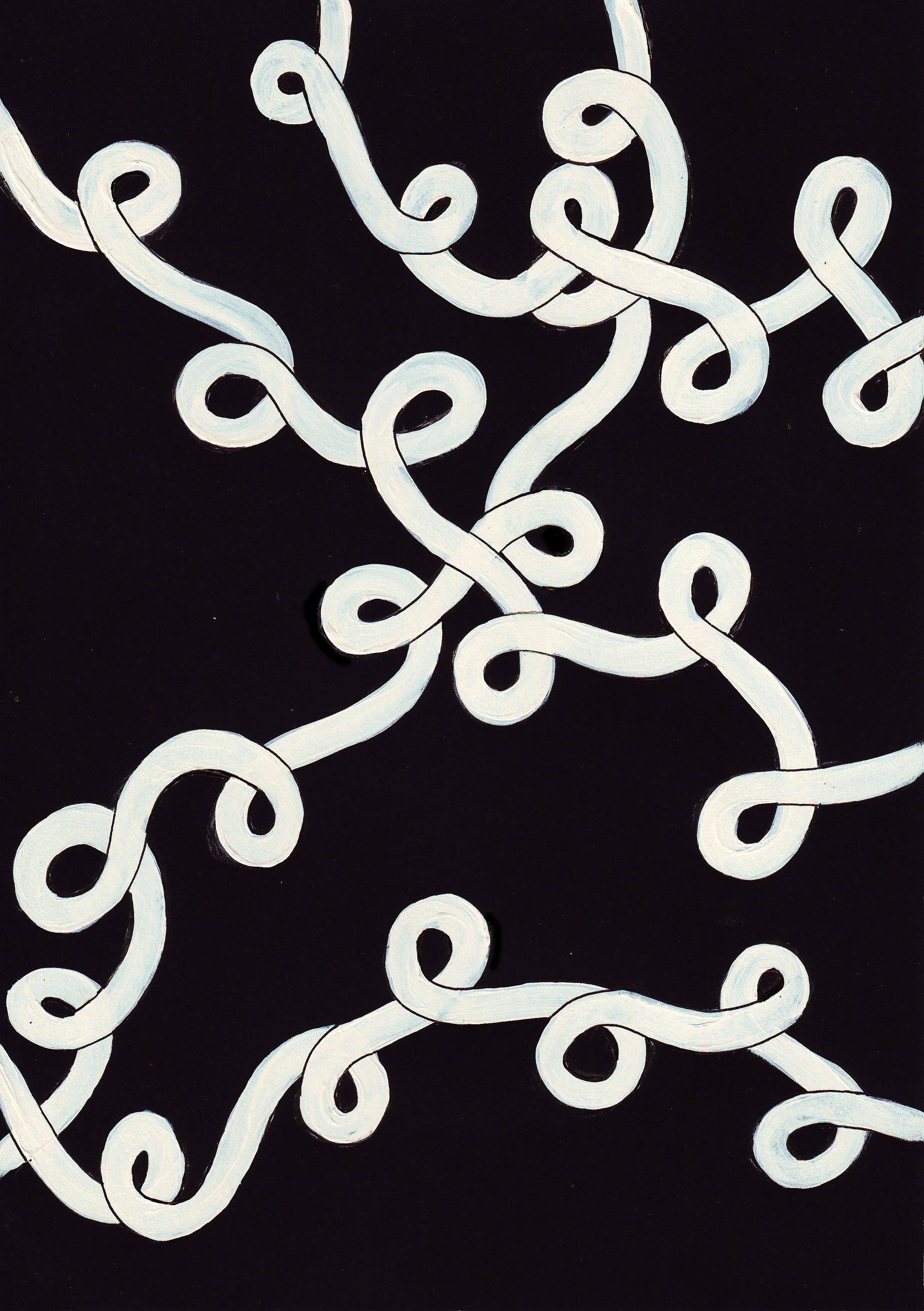

The physical and aural veils of the Vagina Whisperers echo the flayed membranes of Gilbert’s Shedded Skins (inspired by the Jungian concepts of the shadow and golden shadow, and Mesopotamian goddess Inanna’s journey to the underworld) hanging from its façade. They mark transitions and crossing points. Beautiful and intricate boundaries, they confront the viewer with the urge to delve deeper, but it’s an urge carries the implication of transgression. Their existence is an enticement, but also a line of consent.

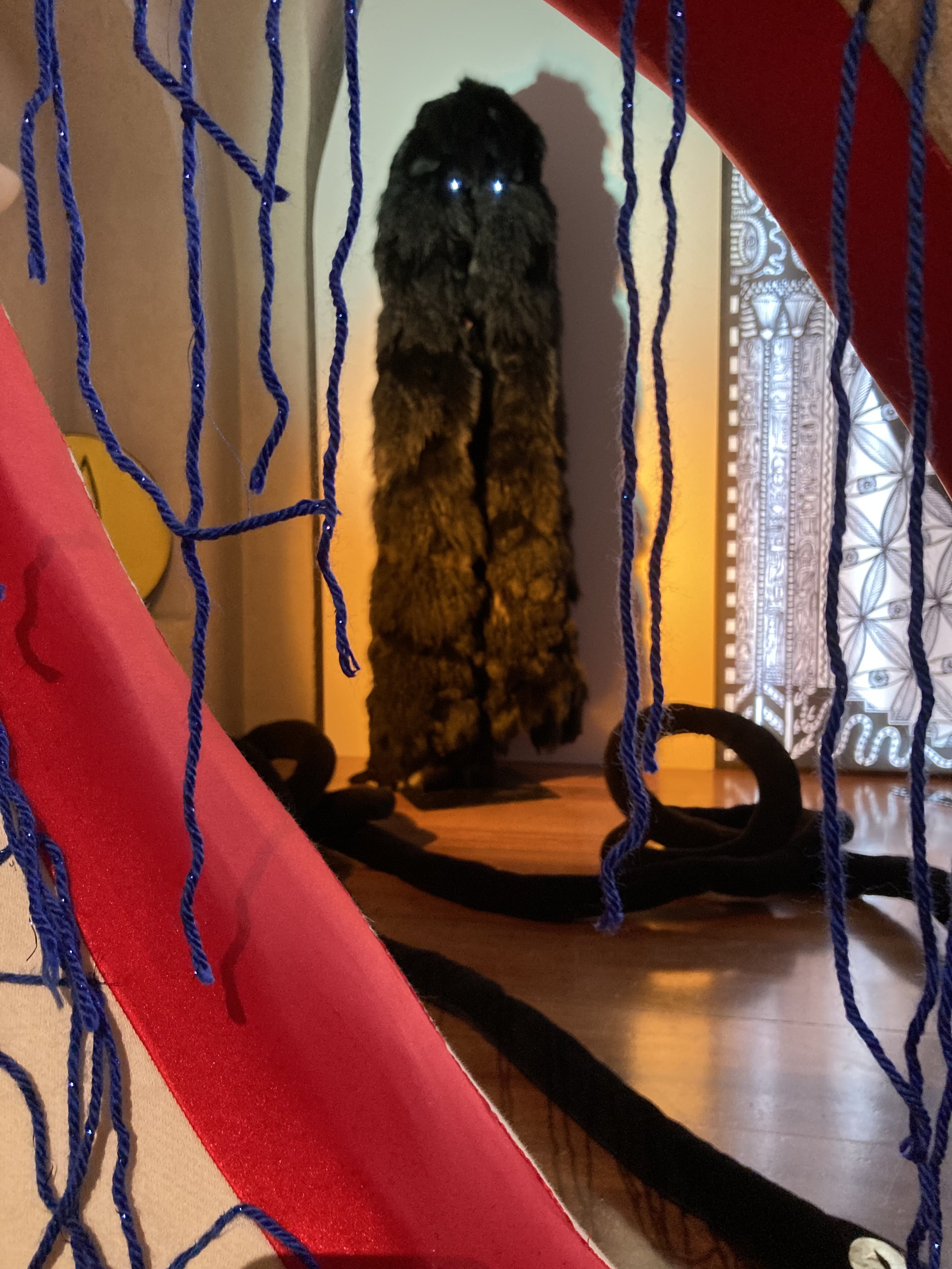

To those crossing The Vesica’s threshold or merely peeking below its surface from outside, Gilbert has created what she describes as a mystery theatre, a hallucinogenic glimpse into the world of dreams and the subconscious, populated by individual works animating aspects of a practise suffused in archetypal languages and ancient symbolisms. The Penetrable Man reclaims the notion of Adam’s Rib, by creating a man from one of Gilbert’s vagina sculptures. Inspired by the Wound Man, a medieval diagram of a sliced, bitten, stabbed and bleeding figure used as a reference for surgeons, this image of a brutalised body was designed not to inspire horror or pathos, but the reverse. Each of the lesions and wounds is part of a visual index of ailments, with accompanying cures. The Wound Man is a manual for the miracles of medical craft. Reinterpreted by Gilbert as a padded and disjointed figure studded with vaginal wounds and eyes, this is a male body made vulnerable, challenging power dynamics and the banality of sexual violence.

Gilbert’s work may be humorous and sly, but it’s also unflinching in bearing witness to physical and emotional abuse, and biological grief. It counters the trauma with its antidote, the power of resilience, the talismans of the sacred feminine and procreation. Personal, but also species, survival.